As modern online marketers who are totally in tune with everything that happens on the world wide web, we should — undoubtedly — be able to teach others how all of this “internet" stuff works.

As modern online marketers who are totally in tune with everything that happens on the world wide web, we should — undoubtedly — be able to teach others how all of this “internet" stuff works.

The issue, of course, is that many of us can’t explain it … at least not accurately, or succinctly, or eloquently. And considering we rely on the internet so freakin’ much, I figured it was time we nail this one down.

As it turns out, explaining how the internet works in a way that even the most internet-agnostic person can understand is easier said than done. As Google’s executive chairman, Eric Schmidt, once observed: "The internet is the first thing that humanity has built that humanity doesn’t understand."

Challenge accepted, Schmidtty.

My new goal in life, starting with this article, is to help humanity understand the internet.

Let’s get started, shall we?

In the Beginning …

There was Al Gore, chief architect supreme of the internet.

Just kidding, that story is merely an internet myth (based on a clumsily stated/poorly interpreted quote).

In reality, lots of folks contributed to the invention of the internet over a span of several decades. From Nikola Tesla describing a "World Wireless System" at the turn of the century, to researchers coming up with plans for searchable media databases in the ’30s and ’40s, there have been many stepping stones along the way to the modern internet.

What really got the ball rolling, however, was the Cold War. Out of fear that the Soviets could destroy America’s telephone system (thereby rendering long-distance communication impossible), the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) began looking for alternatives.

M.I.T. scientist J.C.R. Licklider came up with a solution in 1962: an "intergalactic computer network" that would allow for communication on a global scale.

What Licklider described would eventually become the modern internet. However, in order to make it happen, scientists would first need to come up with a new technology: packet switching.

Packet Switching: Technology That Makes the Internet Possible

Developed in the mid-’60s, packet-switching technology brought communication into the digital age.

At the time, traditional communication networks — like the nation’s telephone system — relied on analog, circuit-switching technology. (If you use a landline phone, you still rely on this technology, by the way.) With a circuit-switching system, a dedicated line allows for transmission of data from one point to another. It’s a continuous connection, and data is always received in the order in which it’s sent.

In comparison, with packet-switching technology, data is first divided up into smaller chunks called "packets." In addition to carrying data, each packet contains destination information, so it knows where it’s going. This means that packets can be transmitted individually, follow different routes (there’s no dedicated line), but ultimately arrive at the proper destination. Once there, all of the packets can be recompiled to form the original data-set or message — regardless of the order in which those packets arrive.

Ugh.

That’s a simplified explanation, and it’s still a bit confusing. Let’s try this again …

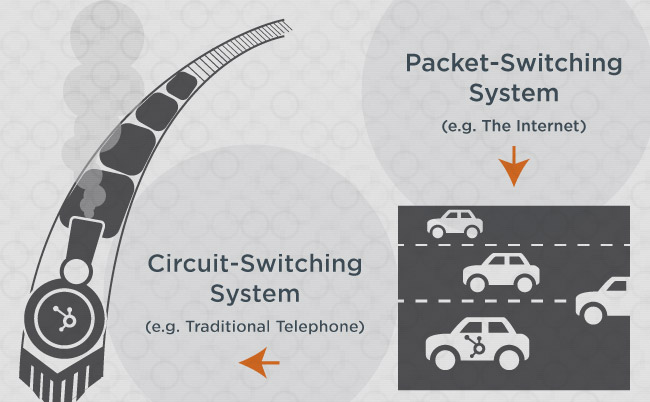

Circuit switching is like a train riding along train tracks, whereas packet switching is like cars driving on the highway.

A train carries its train cars (the data) in a set order, and rides along a track (the dedicated line) that takes it from point A to point B. Other trains can’t use that track at the same time as the first train because, ya know, they’d crash. That’s circuit switching.

Now, onto to packet switching, i.e. cars on the highway. Multiple cars (the data packets) can drive on the same highway (the line or channel) at the same time. There’s no set order, and cars can change lanes at any time. Ultimately, all of those cars can get from point A to B, albeit at slightly different times.

This train/car comparison makes the benefits and drawbacks of circuit switching and packet switching easier to grasp, too.

For example, with a train (circuit-switching system), you don’t have to worry about traffic: There’s a dedicated track, so no other trains will be clogging up your journey.

The downside, of course, is that if anything happens to that dedicated track — even to a small portion it — you’re in deep doo-doo. You have one track: If it breaks, your journey is over.

With cars (packet-switching system), travel is more efficient in the sense that one highway can accommodate multiple travelers. What’s more, if one lane of the highway happens to close, that doesn’t mean your journey is over: you can simply move to another lane.

The downside here is traffic. If too many cars (data packets) get on the same highway (channel), those cars will move more slowly, and may eventually stop.

Ever wonder why your internet can be slow, but a land-line phone always delivers data (voice data, that is) in real-time? You can think of the former as cars stuck in traffic on the highway, while the latter is a train rumbling down an empty track.

You Down With TCP/IP?

Unfortunately, packet-switching technology alone can’t explain how the entire internet works.

To help you better understand what’s missing, let’s check back in with our friends at ARPA …

By the early 1970s, ARPA’s packet-switching computer network (the imaginatively named "ARPAnet") was growing and connecting with other packet-switching computer networks around the world.

There was only one problem: Computers operating on all of these disparate computer networks couldn’t communicate directly with one another. There wasn’t a single, worldwide internet. Instead, there were a bunch of mini-internets.

To solve this problem, computer scientists developed the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the Internet Protocol (IP).

TCP is responsible for dividing data into packets at one end of a transmission and reassembling those packets at the other end.

IP, in comparison, is responsible for the formatting and addressing of the data packets being sent. That’s why each host computer on the internet needs an IP address: a unique, numerical label that distinguishes one host from another. Without IP addresses, data packets wouldn’t be able to get to their proper destinations.

When implemented together, TCP/IP is the communication language of the internet, and it was the key to making the internet a truly worldwide network.

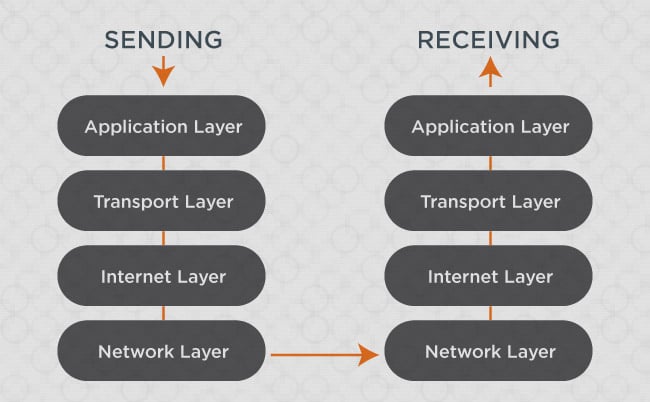

Modern TCP/IP networks use four distinct layers in order to transmit data, and that data always moves from one layer to the next.

- First, there’s the application layer, which is responsible for interfacing with computer applications such as web browsers and email clients.

- Second, there’s the transport layer. This layer is where the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) goes to work dividing data into packets (and, on the receiving end, it reassembles that data).

- Third, we have the internet layer, where the Internet Protocol (IP) assigns address information and determines the route the data will take.

- Finally, we have the network layer, wherein physical hardware actually carries the data via wire, fiber, radio etc.

When we send data across the internet, that data goes through each of these four layers in sequence, starting with the application layer. On the receiving end, however, the sequence is reversed. The data you send arrives via the network layer, it then goes through the internet layer to confirm it’s in the right place, the transport layer reassembles all of the data packets, and — finally — it reaches the application layer, and a recipient is able to view the data in an application.

In diagram form, someone sending a message across the internet would look like this:

Now, to ensure we’re all on the same page here, let me make this quick simile: Sending data across a TCP/IP network is like sending a letter through the mail via the postal service.

- In the application layer, you’re writing the actual letter that you’re going to send.

- In the transport layer, you’re packaging that letter in an envelope.

- In the internet layer, you’re writing the address of the recipient on the envelope, as well as your return address.

- And finally, in the network layer, you’re putting the letter in the mail so postal workers can deliver it.

Welcome to the World Wide Web

The TCP/IP breakthrough in the ’70s meant that scientists in the ’80s got to have a ton of fun sending data to each other across a truly global network. However, there was still a big piece missing from the modern internet we know and love today: the World Wide Web.

While we often use the terms "internet" and "web" interchangeably, the reality is that the latter is a subset of the former: the web is a collection of all of the public websites on the internet.

Up until the ’90s, there were no websites, and no World Wide Web to collect them. That all changed with software engineer Tim Berners-Lee, who first proposed the concept of a World Wide Web in 1989. By the end of 1990, he had successfully launched the first web page.

Berners-Lee was on a mission to create a more useful internet — an internet that wasn’t simply a network for sending and receiving data, but a "web" of data that anyone on the internet could retrieve. In order to accomplish this, he needed to develop three essential pieces of technology, which are:

- HyperText Markup Language (HTML): This is the standard protocol for publishing content on the web. It’s used to format text and multimedia documents as well as link between documents.

- Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Just like every computer on the internet gets a unique identifier in the form of an IP address, every resource on the World Wide Web gets a unique identifier in the form of a URI. The most common type of URI is the Uniform Resource Locator, or URL (also known as a "web address").

- HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP): HTTP is responsible for requesting and transmitting web pages. When you enter a URL into a web browser, you’re actually initiating a HTTP command to go find and retrieve the web page specified by that URL. In relation to a TCP/IP network, HTTP is part of the application layer, as specific applications — namely, web browsers and web servers — use HTTP to communicate with one another.

So there you have it, the key ingredients of the World Wide Web.

Of course, with the advent of search engines, entering in exact URLs in order to retrieve web pages has become unnecessary: We can now simply instruct the search engines to crawl the web (or more accurately, an indexed version of the web) in order to find what we’re looking for.

To sum this all up with an an easy-to-understand simile: The World Wide Web is like a giant library … that is staffed by friendly robots.

The library is loaded with books (web pages) that all follow a unified format (HTML). Every book has a cover, a binding, pages, and so on.

If you know the call number (URI) of the book in the library’s cataloging system, you can simply give that number to a friendly robot (HTTP) who can then retrieve the book for you.

If you don’t know the call number, you can search through the library’s index (like a search engine) using the information you do know, such as title, author, or year published. Once you’ve identified the book you’re looking for, you can then hand the call number off to the friendly robot for retrieval (i.e. click on the search result link and initiate an HTTP command).

Internet = Understood

Alright, folks. We’ve successfully covered the basics of packet switching, TCP/IP, and the World Wide Web, which means you now completely understand how the internet works.

OK, definitely not true. But at least (I’m hoping) you have a slightly better understanding of it.

The reality, of course, is that the internet is a technological beast, and I am but a mere marketer. So, if you want to dive deeper into how all of this stuff works, let Google be your guide and get searchin’!

If, on the other hand, you’re looking for information about marketing your business on the internet, we’ve got you covered. Check out our recently updated resource, The Essential Step-By-Step Guide to Internet Marketing.

![]()